This phrase has often been reserved for women in complicated relationships, however, it is important to appreciate that the complexities of relationships are realized by all across age, gender, race and class. The social difference has always been the burden placed on women to carry (essentially, religiously, and culturally) the decorum of the relationship, hence the assumption is often “why do women stay” because exploring “why men stay” would disrupt masculinity ideals.

I will admit that in thinking about the subject matter, my reference was in the symbolic and in the abstract to women – the stories I have come to know, the negotiations within my own self, the politics surrounding women in relationships and the degradation of women in social media spaces for “failed” or “complex” relationship experiences. So, why do people stay? The simplistic response may reference being internally conflicted regarding their supposed “duty” to love, serve, respect, honor and appease the social milestone expectations placed on the ability to commit, love and be loved.

In unpacking this, there are a few things I would like you and I to hold in mind as we collaborate in understanding. These are attachment, historic relational trauma, and emotional awareness as well as emotional regulation. All of these tend to present as significant strongholds in the resolve of complex or abusive relationships. When we speak about the cycle of abuse, literature simplifies it as the process of negotiating, tension, incident, calm and reconciliation. What we miss out on is the stages of grief cycle with that abuse, the disrupted internal condition of one’s sense of safety and security which is part of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as well as the tremendous resolvement of parts of our own experiences that remain raw and unprocessed.

Our sense of the world and understanding relationships begins in the family, which makes the family as a system both powerful and equally disruptive in our understanding of self and others. Attachment is the natural process of response to a primary caregiver, it is what teaches us even before we can formulate an understanding, who is safe and who is unsafe because of our bodily responses to that person – ease or adrenaline. Many of us can tell of the adults in our lives that we preferred and those that we did not because of the way we were attached to them. We then go along to experience other social systems that can either be a corrective experience or reinforce the assumptions we have as an extension of our family lives. In peer relationships, engagement with authority figures, establishing romantic attachments, we quickly learn betrayal, disappointment, shame, humiliation, and loyalty as some of the feelings that can come from our attempts to relate. Some of these experiences are inherited into our sense of self and start to inform our identity. We then go on to meet more people and expand our social networks in a way that challenges our worldviews and gives us alternative ways of thinking intra-personally as well as interpersonally. We then develop this awareness of ourselves in profound ways that call for learning and unlearning CONSTANTLY. Awareness constantly challenges how regulated you are as a person in trusting what you feel, relaying it in a manner that shows maturity, and being open to receive feedback or even be challenged about the manner of your approach to life.

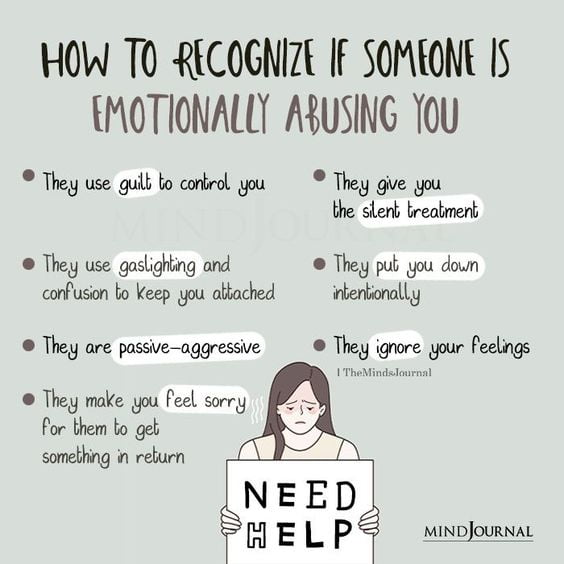

All this seems like a straightforward life-cycle experience, but it presents differently when we introduce instances of relational hostility, doubt, lack of esteem and power. I have come to appreciate that much of the resolve of why people stay is because we are spending a lot of time negotiating what we know, what we have come to know, and what we are yet to know about relationships. People do not present as hostile in the beginning lest they drive away the prospects of a meaningful relationship, however, when they quickly resolve what they stand to gain and lose against their own ego, things can change. “Date kind people ” – a common phrase that has the potential of shaming the person on the receiving end of abuse makes it seem like one may have been caught up in being in love than who they were in love with. This denies the fact that people are performative and tend to settle into who they are once they get a sense that loyalty has been established. Here is where the power play begins, at loyalty, at the appreciation that you have given the person an impression of security and consistency, then taking that away which sends them into a spiral. Whilst people negotiate what may have changed, the abuse persists that they suddenly lose sight often of what it means to piece the patterns together. The cycle of abuse depends on chaos – being lost in one’s mind whilst weighing up whether an incident is fleeting or whether it can be attributed to one’s character.

Assumptively, people stay because they need to disrupt their previous sense of security and go against what their mind, heart and body had come to know of a person. They split often between love and hate, admiration, and fear, as well as who their partner is becoming versus what they thought they knew. Abuse introduces an unexpected adjustment to what was an established truth – suddenly the person who was reliable for affection possesses the ability to harm deeply and intentionally. People also stay because they realise that ending relationships means giving away the best parts too and that is what makes them equally cycle between resolved and conflicted.

Others stay because quite frankly leaving has been deemed as more dangerous – threats of being killed, humiliated, sabotaged and punished are often too intimidating. The private vs. public discourse (abantu bazothini) weighs heavily and contributes to the silencing of many. Although many might say live your truth, at times, there is a great price to pay and this leaves many feeling helpless. People who stay also believe that certain phases of the relationship are seasons of testing and that this may just be an attack from evil spirits and spend much of their days pleading for spiritual interventions that may also reinforce endurance (ukubekezela).

Providing support

- Importantly, understand that relationships gradually grow from affection to affliction. When holding space for another, realise that they may need to be affirmed that they have loved well – as often in the discrediting of their character, they are led to believe that they failed to uphold the relationship.

- Realize that until one is committed to change, all other efforts are mere guidance. Once might read this and this, it is so tedious to support cycling – but equally so, you may just be the person they tell enough times until they start to hear what they are saying and extend grace to themselves.

- Be resourceful in terms of tangible support should the survivor be punished by being denied privileged access to material things and lifestyle expectations.

- Collectively support a survivor by shining a light on the secrecy that tends to benefit the abuse.

Getting help

- There are organizations that assist individuals that are struggling with negotiating their exit from unsafe relationships.

- POWA, TEARS, Lawyers Against Abuse, Sonke Gender Justice, CSVR, SADAG, Lifeline.

- Consult a psychologist or counsellor who might be able to assist in managing the process with you – to support your doubt, to build up your confidence and to restore your sense of trust in self and your emotional experience.

- Exposing abuse on social media may seem safe as the sense is that one may have exposed the prime suspect in the event of harm, but stranger sympathy can take an unfortunate turn when survivors are guilted, further shamed and isolated. Social media is not an entirely safe space – it may be proactive in seeking justice, but just as trends subside, so does the resolve.

- Lean into organizations that might be supportive, church counselling, community centres, and clinics that might assist in linkage to care.

No Comments