This past weekend, something truly extraordinary unfolded in the streets of eNtokozweni (Machadodorp).

For the 10th anniversary of the My Body My Space: Public Arts Festival (MBMS), the town came alive in a way few could have imagined—a whirlwind of color, movement, and powerful performances that redefined what art can do. What started as a small celebration of creativity a decade ago has now grown into a movement that is shaking up the very foundation of how we think about art, bodies, spaces, and the environment.

It wasn’t just a festival. It was an explosion of imagination that took over unexpected corners of the town—from coffee shops and libraries to funeral parlours—transforming them into living canvases where everyone was invited to participate. Art was no longer an elite, reserved experience—it was for everyone, everywhere. Hundreds gathered in awe as the town became an immersive experience, with powerful performances that tackled everything from the urgency of climate change to the complexities of identity and race.

One of the most mesmerizing performances came from Louiseanne Pui Chi Wong, a choreographer and dancer born in Hong Kong and now based in the UK. Her piece, I Am. Am I, was an emotionally charged journey through displacement, identity, and unlearning the societal conditioning that comes with living in Hong Kong.

Using dance, circus, and bilingual voice, Wong wove a narrative about the East Asian diaspora, confronting layers of racism and the quest to belong. Her performance wasn’t just an artistic expression—it was a personal and political statement about navigating the complexities of identity and the challenges of a world that often doesn’t make space for those who are different.

The festival also brought us Twice Euphoric’s The Life and Death of an Orange: Case Study with uDonga, a performance that had audiences peeling back the layers of life and death itself. The performance challenged us to consider when life truly begins and ends—”Once you’ve peeled an orange, you cannot put it back together again,” they provocatively declared. Through a striking combination of memory, monumentality, and the exploration of dualities like pain/pleasure and desire/repulsion, this performance had audiences contemplating the irreversible, yet beautiful, nature of transformation.

But it wasn’t all about the performances. The entire festival weekend was a testament to what art can do when it is free, accessible, and rooted in community.

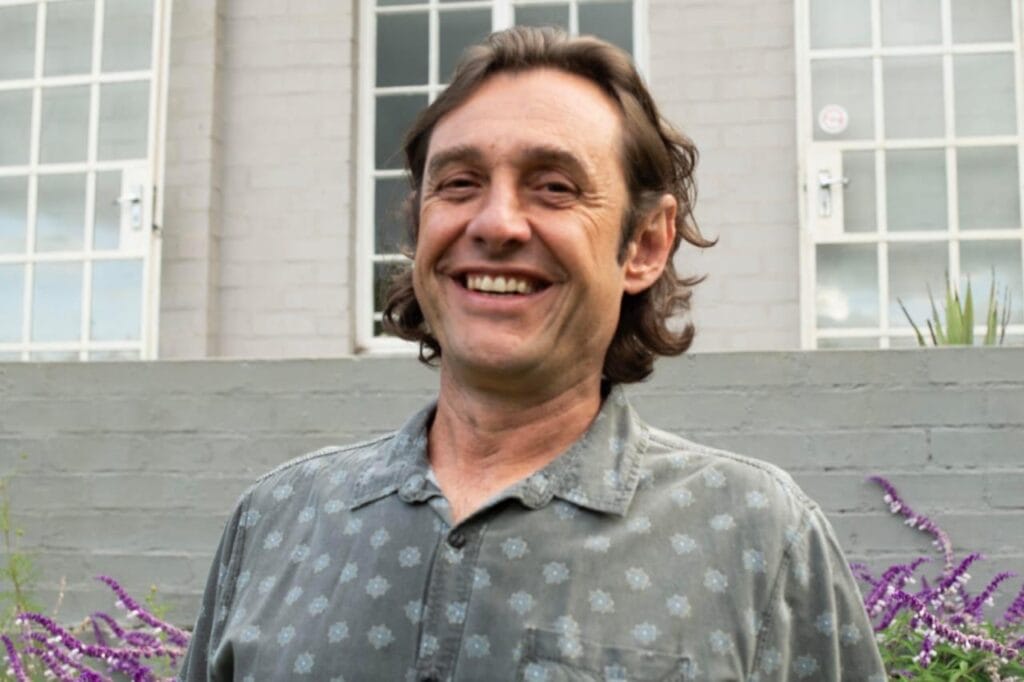

Under the visionary leadership of PJ Sabbagha, Managing and Artistic Director of both FATC and MBMS, the festival has spent the last decade breaking down barriers. Sabbagha believes that art should not be confined to elite spaces: “It must be a tool for change, a way to democratize and decentralize the experience of performance,” he asserted.

And that’s exactly what MBMS did—it brought art to the people, made it personal, and made it matter.

“We are here to make art accessible and to bring it to spaces where people wouldn’t traditionally have access to it,” Sabbagha continues. “Art has the power to challenge societal norms, to be a reflection of the times we live in, and to create a lasting impact. The festival is about creating spaces where people feel empowered to question and to be part of something greater than themselves.”

This year also marked the 30th anniversary of the Forgotten Angle Theatre Collaborative (FATC), which has been at the heart of the festival’s growth. The festival’s Arteries Programme and CNS Programme activated spaces across Emakhazeni, from schools and churches to cultural heritage sites, making the performances accessible in ways that traditional venues simply can’t.

Through its LEAP (Local Education in Arts Programme), MBMS also created a platform for youth, women, and people with disabilities to explore and develop their artistic talents, ensuring that the next generation of artists in rural Mpumalanga are not only seen but nurtured.

Mongezi C. Makhalima, another key figure behind MBMS, captured the heart of the festival’s mission when he said, “We do this because we love it, not because we are looking for benefits. We do this for the people, for growing the arts, and for the children who have dreams.” His sentiments echo the words of Nina Simone, who famously said, “The work of the artist is to reflect the times.” And right now, Makhalima believes, the time is ripe for rebuilding communities—a cause that both FATC and MBMS are passionately committed to.

“We don’t do this for the accolades or recognition,” Makhalima continues. “We do this because art is a powerful tool to reflect the times and rebuild our communities. It’s about creating a space where people, especially the youth, feel seen, heard, and empowered to dream. The forgotten angle and My Body My Space Collaborative are here to help create that space, to make sure our voices and our experiences are represented.”

As the weekend culminated at the picturesque Kloppenheim Country Estate, nestled among rolling green hills, the atmosphere was electric, reflecting the undeniable power of art to ignite change. From the vibrant streets of eNtokozweni to the peaceful countryside, the festival reminded us all of art’s incredible ability to reshape our world.

The My Body My Space Festival is more than just a celebration—it’s a force for transformation. It’s about shifting conventions, breaking barriers, and using art to build a more inclusive, more conscious world. And with the leadership of Sabbagha and Makhalima, the next decade of MBMS promises to be even more groundbreaking. One thing’s for sure: this festival is just getting started.

No Comments